Joe Di Maggio’s Early Years

Joe Di Maggio’s Early Years

Joe Di Maggio: The New “Bambino” — 1937

Di Maggio is no Pop-off Guy — 1941

Di Maggio Weds Marilyn Monroe at City Hall — 1954

Lefty O’Doul Day at Seals’ Stadium — 1938

Joe Di Maggio Dead at 84 — 1999

|

Joe Di Maggio, the Yankee Clipper

“I would like to take the great Di Maggio fishing,” the old man said. “They says his father was a fisherman. Maybe he was as poor as we are and would understand.” Ernest Hemingway

“The Old Man and the Sea”

His name was Giuseppe Paolo Di Maggio and he came from the community of Isola Delle Femmine, an islet off the coast of Sicily, where the Di Maggios had been fishermen for generations. Known as Zio Pepe, he migrated to the town of Martinez, a small fishing community some 25 miles northeast of the Golden Gate. In 1915, hearing of the luckier waters of San Francisco, he packed his fishing boat with his furniture and his family and docked at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco.

He found a flat on Taylor street, near the Wharf, and there he lived and worked at the sea and began to raise his large family. His children, in order, were Nellie, Mamie, Tom, Marie, Mike, Frances, Vince, Joe Jr., and Dominic. He wanted two of the boys to help him in the fish business, one to be a great opera singer, one to be a lawyer because “he wore glasses,” and one to be a bookkeeper, “because you can sit down.”

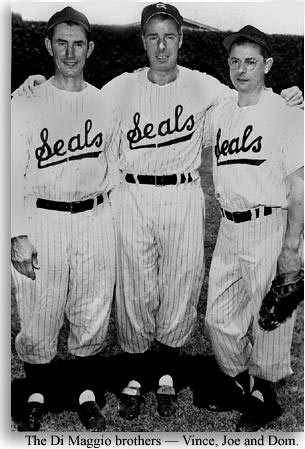

Instead three of the sons went on from Fisherman’s Wharf to become the greatest baseball playing family in the history of the game, one of them being the immortal Joe Di Maggio, the Yankee Clipper. In 13 years of baseball from 1936 to 1949, this son of an immigrant fisherman earned an estimated total of $704,769 playing for the New York Yankees team.

When the elder Di Maggio came to Fisherman’s Wharf from Martinez the younger Joe was only one year old. Fisherman’s Wharf in those days was placid and picturesque, but there was also a competitive undercurrent and struggle for power along the pier. At dawn the boats would sail out for their catch, and then the men would race back with their hauls, hoping to beat their fellow fishermen to shore and sell it while they could. Some 20 or 30 boats would sometimes be trying to gain the channel shoreward at the same time and a fisherman had to know every rock in the water, and later, know every bargaining trick along the shore, because the dealers and some restaurateurs would play one fishermen off against the other, keeping the prices down.

In time the fishermen became wiser and organized, pre-determining the maximum amount each fisherman could catch. But, there were always some men who, like the fish, never learned and sometimes heads were broken, nets slashed, gasoline poured onto their fish and flowers of warning placed outside their doors.

Those days were ending when the elder Di Maggio arrived and he wanted his five sons, at first, to succeed him as fishermen. The first two did, Tom and Mike. The third, Vincent, liked to sing. He sang so well, and his fame spread in the Italian community, that the great banker A.P. Giannini heard him and offered a plan to send him to Italy for tutoring. But, there was not enough money around the Di Maggio household and they hesitated, and Vince never went. With the other boys it was different. Joe tells about it in his autobiography, Lucky to be a Yankee.

“I was born in Martinez, but my earliest recollection was of the smell of fish at Fisherman’s Wharf, where I was brought up. Our main support was a fishing boat, with which my father went crabbing. If you didn’t help in the fishing, you had to help in cleaning the boat. “I was born in Martinez, but my earliest recollection was of the smell of fish at Fisherman’s Wharf, where I was brought up. Our main support was a fishing boat, with which my father went crabbing. If you didn’t help in the fishing, you had to help in cleaning the boat.

“Baseball didn’t have much appeal to me as a kid, but it was better than helping Pop when he was fishing, or helping clean the boat. I was always giving him excuses, principally that I had a weak stomach, but he insisted I was ‘lagnuso’ (lazy) and to tell you the truth, I don’t know which he thought was the greater disgrace to the family, that a Di Maggio should be lazy or that a Di Maggio should have a weak stomach.

“There was a lot of us Di Maggios, nine in all. Pop worked on a two-year scale and everybodys clothes fit everybody else, which meant that only Nellie, the oldest girl, and Tom, the oldest boy, ever got a chance to wear new clothes. Hand-me-downs outfitted the rest of us. Pop didn’t like baseball in those days. ‘Too many shoes, too many pants,’ was his description of our national past-time. Even with plenty of hand-me-downs, the Di Maggios in those days couldn’t reconcile themselves to the shoes I wore out or the pants I tore in my baseball cavorting. Bocci was pop’s game, an Italian version of lawn bowling.

“Baseball to me in those days was merely an excuse to get away from the house and away from the chores of fishing. When Pop gave up trying to make me work on the boat, I gave up playing baseball in the sand patch by the Wharf, and tried my hand at selling newspapers, a job my father declared suited me perfectly since it consisted mostly of standing still and shouting.

“Vince, who had been far more successful than I in baseball, had quit high school to help support the family, although my mother’s advice was to continue his education. Two years later, I followed Vince. Up to the time my baseball playing had been sketchy. In fact, I almost stopped playing when I was 14. Our home was by Fisherman’s Wharf, close to the old North Beach playground, where I had my first baseball experience at the age of ten. I was third baseman in those days and played well enough to be on the usual teams with the kids around my block.

“Pop, having despaired of my ever becoming a fisherman, urged me to study bookkeeping. ‘It’s a job you can do sitting down,’ said Pop significantly, for he was convinced I was lazy.

“Vince, meanwhile, was making good in a big way, or so it seemed to me. He had been signed by the San Francisco Seals and farmed out to Tucson. I was a pretty cocky kid in those days and I said to myself, ‘If Vince can get dough for playing ball, I can, too.’ As a matter of fact, Vince often pleaded with me to take the game more seriously, and it was his idea that I could play well enough to make money at it.

“Some of the kids around the block decided to get up a team and go in the Boys Club League, and we won the championship in our division. There was an olive oil dealer in our neighborhood, named Rossi, who took our club out of the Boys Club League and outfitted us with better uniforms and equipment than we ever had before. He was a real fan and took great pride in having a ball club of his own. We won the championship in a play-off, in which I hit two home runs. As a reward for this, I received two gold baseballs and two orders for merchandise worth about $8 each. It was my first financial return from baseball.” “Some of the kids around the block decided to get up a team and go in the Boys Club League, and we won the championship in our division. There was an olive oil dealer in our neighborhood, named Rossi, who took our club out of the Boys Club League and outfitted us with better uniforms and equipment than we ever had before. He was a real fan and took great pride in having a ball club of his own. We won the championship in a play-off, in which I hit two home runs. As a reward for this, I received two gold baseballs and two orders for merchandise worth about $8 each. It was my first financial return from baseball.”

With his brother playing for the San Francisco Seals, Joe began hanging around the ball park and to his delight was invited to the Seals training camp for the 1933 season. Joe made the team and sports writers described him as “a tall gangling youngster, all arms and legs and like a frisky colt.” His batting prowness soon asserted itself and, in his first year, Joe was attacking the [Pacific Coast] league record for hitting in successive games. There were 10,000 people in Seals Stadium on July 4, 1933, including Joe’s family, to watch him try for a hit in his 49th straight game, which would break a long standing record. In the first inning Joe singled to center field and the record was broken.

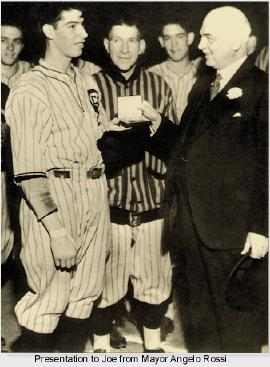

“Then the game was stopped,” Joe recalled. “Angelo Rossi, Mayor of San Francisco, came on to the field to congratulate me personally, which was quite a thrill to a kid who couldn’t be able to vote for him for three more years.

“My whole family was on hand and my mother hugged me for joy. She didn’t understand much about baseball but she realized I was being honored and that was enough for her. The publicity attendant on my batting streak converted Pop to baseball. At first, he thought it was silly for people to dress up in short pants with spikes and gloves. Then he couldn’t see me, a kid, making good against ‘all those older men.’ He forgot about this and even forgot about bocci. ‘Bocci ball?’ Pop would say, ‘No money in bocci ball. Baseball, that’s the game.’ ”

Joe’s hitting streak finally ended at 61 games. He was then presented with a watch by Mayor Rossi and a traveling bag from his friends at Fisherman’s Wharf. Joe secretly was more pleased with the traveling bag.

The traveling bag came in handy because Joe was then signed for the 1936 season to play with the New York team, the start of a brilliant career that took him for the first time away from Fisherman’s Wharf he knew so well. Baseball opened many doors for Joe. At 6 feet, 2 inches, with brown eyes and black hair, he struck an impressive role both on and off the field. Joe immediately broke into cafe society and was named one of the nation’s ten best dressed men. But, Joe never forgot San Francisco, nor they him. After his first season with the Yankees, Joe returned home to a hero’s welcome.

“They had a brass band to meet me at the station,” recalled Joe. “My parents were crying like children and everyone was shouting ‘DiMag is back.’ All the fellows I’d grown up with at Fisherman’s Wharf were there and they hoisted me on their shoulders and took me to an automobile which carried me to City Hall. There Mayor Rossi made a speech of welcome, telling me how much I’d done for San Francisco. If I were any kind of speaker then, which I was not, I could have told the Mayor that San Francisco had one a lot for me, too.”

While Joe was beginning to hit home runs and break more records, the third Di Maggio, this one Dominic, was making his way up the same baseball ladder. He was the smallest and youngest of the Di Maggios. “I was determined to become a big leaguer,” said Dom, “to disprove all those cracks that I was being given my start just because of my brothers.” Wrote one cruel sportswriter: “He is the tail on Joe’s kite.” Dom was named “most valuable” player on the Seals and in 1940 went to the Boston Red Sox where he was known as the “Little Professor.” He soon moved out of Joe’s deep shadows, which blanketed him in his early years and ran up an impressive record of his own.

“I think Pop’s pride and joy was Dom,” said Joe. “When Dominic was in short pants, Pop wanted him to become a lawyer because ‘he wears glasses.’ Dom, who never looked as though he’d grow to be five feet, gained five inches in his 18th year and promptly turned to baseball. As a purely personal opinion, I think he’s the best defensive outfielder I’ve ever seen.”

Dominic fished more than either of his baseball brothers, Vince or Joe. He enjoyed the clear moonlit nights, the easy motions of the fishing boat and the harvest of fish that poured from the nets. He often went out with his brother Mike and on one occasion had a near brush with tragedy. Dominic fished more than either of his baseball brothers, Vince or Joe. He enjoyed the clear moonlit nights, the easy motions of the fishing boat and the harvest of fish that poured from the nets. He often went out with his brother Mike and on one occasion had a near brush with tragedy.

“Mike and I were out this night,” said Dominic, “It was rough and choppy. We had a net out and were rounding a point. Usually the current took us out. This time it carried us in. We never learned why. There was a reef off the point, with just a narrow passage between it and the mainland. Our only choice was to squeeze through. Just as we reached it, Mike cut the net loose, and in we went. There was a strong current. The water came up to the gunwales and we scraped bottom, but we went through. If we’d ever hit or stuck—well, we lost the net but saved our lives.”

Tragedy later struck down Mike in 1953, at the age of 44, when he fell from his boat while fishing in the Bay and drowned.

By now Joe and the Di Maggio family were national celebrities. The elder Di Maggio was always being greeted on the Wharf by friends and strangers alike, who wanted to talk baseball. With three of his sons in baseball Zio Pepe learned enough of the game to carry on conversations about batting averages and who was going to win the pennant.

Zio Pepe developed an uncanny sense of prophecy about Joe’s game. In 1938, he predicted Joe would hit 46 home runs, which he did. Joe crossed him up in 1940. The elder Di Maggio called for 30 home runs, and Joe hit 31. Joe went on to many baseball records. He led the American League in batting in 1939 and 1940 and let in the number of home runs in 1937 and 1948. He batted safely in 56 consecutive games in 1941 for a new record, and he was named the most valuable player in the American League in 1939, 1941 and 1947.

If there was any doubts of Joe’s role as a celebrity outside of the playing field they were dispelled on November 19, 1939, when he married movie actress Dorothy Arnold, whom he met while making a movie in Hollywood. The ceremony was held at St. Peter and Paul Church in North Beach and some 30,000 persons crowded the church inside and outside to see the famed couple. Fans climbed trees and stood on rooftops to catch a glimpse of the couple leaving the church. If there was any doubts of Joe’s role as a celebrity outside of the playing field they were dispelled on November 19, 1939, when he married movie actress Dorothy Arnold, whom he met while making a movie in Hollywood. The ceremony was held at St. Peter and Paul Church in North Beach and some 30,000 persons crowded the church inside and outside to see the famed couple. Fans climbed trees and stood on rooftops to catch a glimpse of the couple leaving the church.

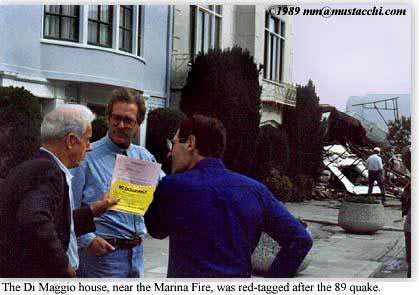

With the baseball Di Maggio’s earning more money than any fisherman ever dreamed, Joe first bough a new home for his folks in the Marina District, and still comfortably near the Wharf. In 1937, the Di Maggio’s decided to open a restaurant on the Wharf, called “Joe Di Maggio’s Grotto,” and the huge electric sign showed Joe in his familiar baseball hitting stance. The walls of the restaurant itself were lined with pictures of Joe’s and Dom’s and Vince’s baseball buddies. Tom took over management of the restaurant and it proved an excellent opportunity for the older Di Maggio to retire gracefully from fishing.

The elder Di Maggio took great pride in preparing meals for baseball players who visited the Grotto during the off season. He often cooked them the Italian dish of cioppino, gave them towels for bibs and told them to dig in with fingers, no knives or forks permitted. The elder Di Maggio took great pride in preparing meals for baseball players who visited the Grotto during the off season. He often cooked them the Italian dish of cioppino, gave them towels for bibs and told them to dig in with fingers, no knives or forks permitted.

Divorce came to Joe and Dorothy Arnold in 1944, and then came his much publicized romance and marriage to film actress Marilyn Monroe in January of 1954. They were married at City Hall in San Francisco and reporters stood on chairs to look over the transom at the judge performing the ceremony. Joe brought Marilyn to live with him in a home near the Wharf in San Francisco. Sometimes they could be seen early in the morning fishing off Joe’s boat, the “Yankee Clipper.” In the evening they could be seen walking along the pier, holding hands and passing by many tourists who failed to recognize the famed couple. Columnists took delight in writing about Marilyn shopping in neighborhood stores and not being recognized.

But all was not rosy. Joe was then 39, and Marilyn, 27, and there was a growing disharmony in their temperaments. Joe had been through his baseball career and he was tired of publicity, while Marilyn was thriving on it. Joe was intolerant of tardiness, while Marilyn was always late. In a much repeated story, Marilyn appeared before some 10,000 troops in Korean to entertain and later exclaimed to Joe: “You never heard such cheering!” and Joe replied, “Yes, I have.”

They separated nine months after their marriage and were later divorced. Marilyn later married, and divorced, playwright Arthur Miller. But after Marilyn’s death it was a sorrowful Joe who made the funeral arrangements. He described Marilyn as a “warmhearted girl that those people in Hollywood took advantage of.” They separated nine months after their marriage and were later divorced. Marilyn later married, and divorced, playwright Arthur Miller. But after Marilyn’s death it was a sorrowful Joe who made the funeral arrangements. He described Marilyn as a “warmhearted girl that those people in Hollywood took advantage of.”

In time, Joe sold out his interest in the family restaurant, though he was seen there on many occasions over the years. He invested his money wisely and took part in a number of business deals. He returned to baseball in 1968 as a coach for the newly transferred Oakland Athletics. Vince, who played on a number of major league teams, retired to live and work as a carpenter in nearby Pittsburg, California. Dom became the most successful in the business world and went to live in a fashionable Boston suburb with his family.

In: “Crab is King”: the colorful stories and the fascinating history of Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, also some favorite Wharf recipes by Bernard Averbuch. San Francisco : Mabuhay Pub. Co., 1973.

Joe Di Maggio Bibliography

Author: Di Maggio, Joe, 1914-

Baseball for Everyone; a Treasury of Baseball Lore and Instruction for Fans and Players. Line illus. by Lenny Hollreister. Advisory board of baseball experts: Carl Hubbell [and others], with a special chapter “How to score,” by Red Barber. New York, Whittlesey House [1948]

Di Maggio, Joe, 1914-

Lucky to be a Yankee. New York, R. Field: Greenberg: publisher, distributors [1946].

Return to the top of the page.

|