San Francisco History 1865-1900

1888 Biography of Henry George

Preface to 4th Edition, by Henry George

Kearney Agitation in California, by Henry George — 1880

San

Francisco’s Early Labor History

The

Museum’s Labor Archives

John

Swett and Early Calif. Education

Biography

of Andrew Hallidie - Cable Car Inventor

|

Progress and

Poverty—a Paradox

By KENNETH

M. JOHNSON

HENRY GEORGE intended the

title to his book to state a paradox; however an additional paradox has

developed. This is the fact that in none of the lists of important California

books has the title appeared. One of the earliest and best known selective

listing of California books is Phil Townsend Hanna’s Libros Californianos;

this was first published in 1931 and was reissued with additions in 1958.

In neither edition is there any mention of Progress and Poverty.

The same is true of The Zamorano 80, perhaps the most distinguished

and critical listing of California books to date. The purpose of this article

is to present the book rather than the author or his beliefs, and to indicate

that Progress and Poverty is an interesting, valuable, and important

part of Californiana as well as a Statement of economic theories.

HENRY GEORGE intended the

title to his book to state a paradox; however an additional paradox has

developed. This is the fact that in none of the lists of important California

books has the title appeared. One of the earliest and best known selective

listing of California books is Phil Townsend Hanna’s Libros Californianos;

this was first published in 1931 and was reissued with additions in 1958.

In neither edition is there any mention of Progress and Poverty.

The same is true of The Zamorano 80, perhaps the most distinguished

and critical listing of California books to date. The purpose of this article

is to present the book rather than the author or his beliefs, and to indicate

that Progress and Poverty is an interesting, valuable, and important

part of Californiana as well as a Statement of economic theories.

In the first place the book

was written and printed in California by a Californian. In the library

of his home at 417 First Street, San Francisco, Henry George, who had first

come to California in 1858, began his book on September 18, 1877.1 It

was a culmination of years of economic study and observation, particularly

of the California scene in the 1870’s.

The eighteen-seventies are certainly

one of the most interesting periods in the history of our state as well

as of our country. They were years of strife, stress, and strain on the

labor and political fronts; on the economic side there were panics and

depressions. The Tweed Ring and Tammany Hall were at their strongest; corruption

in high places was the expected thing. Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Morgan,

and Carnegie were laying the foundation of their fortunes.  In

California, it was the time of the rise of the Workingmen’s Party, Denis

Kearney, and the peak of the anti-Chinese hysteria. It was a period of

contrasts: millionaires were being created from the outpouring of silver

from the Comstock Lode, and millions were being lost through uncontrolled

gambling in Comstock shares. Mansions were being built on Nob Hill, but

there was extensive unemployment. The Bank of California failed. Everyone

knew that the Central-Southern Pacific group completely controlled state

politics, but few knew that the Colton Letters were being written

and would later show the same group buying and selling the members of Congress.

Land was held by a few groups in tremendous acreage. The

Central-Southern

Pacific combination held over eleven million five hundred thousand acres.2

California was forming a new constitution. The period in California has

well been called the “Discontented Seventies.” This then was

the background against which George was writing.3 In

California, it was the time of the rise of the Workingmen’s Party, Denis

Kearney, and the peak of the anti-Chinese hysteria. It was a period of

contrasts: millionaires were being created from the outpouring of silver

from the Comstock Lode, and millions were being lost through uncontrolled

gambling in Comstock shares. Mansions were being built on Nob Hill, but

there was extensive unemployment. The Bank of California failed. Everyone

knew that the Central-Southern Pacific group completely controlled state

politics, but few knew that the Colton Letters were being written

and would later show the same group buying and selling the members of Congress.

Land was held by a few groups in tremendous acreage. The

Central-Southern

Pacific combination held over eleven million five hundred thousand acres.2

California was forming a new constitution. The period in California has

well been called the “Discontented Seventies.” This then was

the background against which George was writing.3

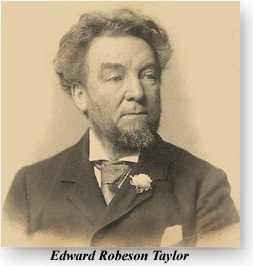

Writing

proceeded slowly: each paragraph was discussed with a small coterie of

friends. Among these were William Hinton, printer and publisher, John Swett,

best known as the founder of San Francisco’s school system, A. S. Hallidie

of the cable cars, and Dr. Edward Robeson Taylor. Dr. Taylor appears to

have been the closest to George and probably participated to a greater

extent than anyone else. If anyone ever deserved the title of a Renaissance

man it was Dr. Taylor: he was successfully a printer, poet, doctor of medicine,

lawyer, mayor of San Francisco, and dean of the Hastings College of Law

for many years. This group worked together to the end that every thought

was crystal clear and stated in a simple direct manner so that anyone who

could read could understand. The work was finished in the early part of

March, 1879, a few days from the adjournment sine die of California’s

second constitutional convention.4 On March 22, 1879, the manuscript

was sent to D. Appleton & Co. in New York; the reply was:

Writing

proceeded slowly: each paragraph was discussed with a small coterie of

friends. Among these were William Hinton, printer and publisher, John Swett,

best known as the founder of San Francisco’s school system, A. S. Hallidie

of the cable cars, and Dr. Edward Robeson Taylor. Dr. Taylor appears to

have been the closest to George and probably participated to a greater

extent than anyone else. If anyone ever deserved the title of a Renaissance

man it was Dr. Taylor: he was successfully a printer, poet, doctor of medicine,

lawyer, mayor of San Francisco, and dean of the Hastings College of Law

for many years. This group worked together to the end that every thought

was crystal clear and stated in a simple direct manner so that anyone who

could read could understand. The work was finished in the early part of

March, 1879, a few days from the adjournment sine die of California’s

second constitutional convention.4 On March 22, 1879, the manuscript

was sent to D. Appleton & Co. in New York; the reply was:

We have read your MS. on

political economy. It has the merit of being written with great clearness

and force, but is very aggressive. There is very little to encourage the

publication of any such work at this time and we feel we must decline it.5

At least at that time publishers

were fairly forthright in their rejections. In turn both Harper’s and Scribner’s

were approached; all declined. George then decided to print the work himself,

and Hinton made his plant on Clay Street available. Type in part was actually

set by George, Taylor, and Hinton. The work was commenced in May, 1879,

and was completed in September. The biographers of George say five hundred

copies were printed; Cowan in his Bibliography indicates that there were

about two hundred copies; in any event the edition was quite small. Copies

were sent to various publishers including Appleton & Co.; this led

to a reply that Appleton would publish the book if given the original plates.

The offer was accepted, and the first trade edition appeared in 1880.

At least at that time publishers

were fairly forthright in their rejections. In turn both Harper’s and Scribner’s

were approached; all declined. George then decided to print the work himself,

and Hinton made his plant on Clay Street available. Type in part was actually

set by George, Taylor, and Hinton. The work was commenced in May, 1879,

and was completed in September. The biographers of George say five hundred

copies were printed; Cowan in his Bibliography indicates that there were

about two hundred copies; in any event the edition was quite small. Copies

were sent to various publishers including Appleton & Co.; this led

to a reply that Appleton would publish the book if given the original plates.

The offer was accepted, and the first trade edition appeared in 1880.

After a slow start the book

became a runaway best seller. It was serialized in Lovell’s Magazine,

a sort of Saturday Evening Post of its day. Translations both authorized

and unauthorized began to appear. There have been German, Swedish, Danish,

Norwegian, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Bulgarian, Yiddish,

Chinese, Japanese, and Korean editions. In 1960 the book was in print in

English and eight foreign language editions.6 The Robert Schalkenbach

Foundation (organized to promote the economics of Henry George) has tried

to estimate the total number of copies printed but without success, except

to ascertain that the number is in the millions. Alice Hackett in her Fifty

Years of Best Sellers, 1985-1945 indicates sales in excess of three

million. 7 Progress and Poverty entered the list of Random House’s Modern

Library in 1938 and has been selling regularly since.8 In 1942 there

was a printing by the Classics Club (a book subscription organization)

with a Foreword by John Kieran. The book is number 8l in the Grolier Club’s

One Hundred Influential American Books Before 1900.

One can count on the fingers

of one hand the number of treatises on economics printed before 1880 which

are in print today; certainly it may be said that Progress and Poverty

has had a wider circulation and a broader influence than any similar work.

The next questions are why

is it important and why has it lasted, In partial answer to both questions

it should be pointed out that in the minds of many there are certain misconceptions

as to the book’s nature and contents. It is far more than an argument in

support of George’s theories on taxation: it is a pungently written and

searching analysis of the economic difficulties of the times. The classical

economists are challenged and specific remedies proposed. California is

used as an example with particular reference to the large land holdings;

however George goes further and considers the world as a whole and the

histories of all times. This work is important because it represents original

thinking and new approaches to old problems. However, its true importance

is not the correctness or incorrectness of its theories, but the fact that

it has led thousands to think about the economic facts of life and the

problems of good government. In this book multitudes have met for the first

time the terms capital, wages, rent, and interest in their economic sense;

here other thousands for the first time have met the early stalwarts, Malthus,

Mill, Riccardo, Quesnay, and Adam Smith. Progress and Poverty finds

its real significance in the fact that it is a book which has provoked

the minds of men.

The book has lasted because

it is readable; it is a book that one can browse in. George was writing

for the masses and not for the college professors. Apt and sometimes homely

illustrations are freely used to drive home points. However, all of this

leads the reader to the most serious and intricate problems of economics,

politics, and to a limited extent law. Following are a few quotations from

the book which suggest its style and method:

There is a delusion resulting

from the tendency to confound the accidental with the essential—a delusion

which the law writers have done their best to extend, and political economists

generally have acquiesced in, rather than endeavored to expose—that private

property in land is necessary to the proper use of land, and that to make

land common property would be to destroy civilization and revert to barbarism.

This delusion may be likened

to the idea which, according to Charles Lamb, so long prevailed among the

Chinese after the savor of roast pork had been accidentally discovered

by the burning down of Ho-ti’s hut—that to cook a pig it was necessary

to set fire to a house.9

There is a lot in the center of San Francisco to which the common rights

of the people of that city are yet legally recognized. This lot is not

cut up into infinitesimal pieces nor yet is it an unused waste. It is covered

with fine buildings, the property of private individuals, that stand there

in perfect security. The only difference between this lot and those around

it, is that the rent of one goes into the Common School Fund, the rent

of the others into private pockets.10

Taxes which lack the element of certainty tell most fearfully upon

morals. Our revenue laws as a body might well be entitled, “Acts to

promote the corruption of public officials, to suppress honesty and encourage

fraud, to set a premium upon perjury and the subornation of perjury, and

divorce the idea of justice.” This is their true character, and they

succeed admirably.11

A corrupt democratic government must finally corrupt the people, and

when a people become corrupt there is no resurrection. The life is gone,

only the carcass remains; and it is left for the plowshares of fate to

bury it out of sight.12

Political Economy has been called the dismal science, and as currently

taught, is hopeless and despairing. But this, as we have seen, is solely

because she has been degraded and shackled; her truths dislocated; her

harmonies ignored; the word she would utter gagged in her mouth, and her

protest against wrong turned into an indorsement of injustice. Freed, as

I have tried to free her— in her own proper symmetry, Political Economy

is radiant with hope.13

Some may urge that Progress

and Poverty should not be included in any list of California books

because it is neither descriptive nor historical. This is obvious; however

it is only half true. The creation of the book and its contents subjectively

reflect California of the seventies in a manner that pure description could

never achieve. Also in a broad sense it is historical; it is a part and

parcel of the times which has survived. Just as an old menu tells us what

people were eating and the cost of living, Progress and Poverty

tells why the seventies were called discontented.

The first edition is easily

recognizable because it is the only one bearing the date 1879 on the title

page and the only one showing Hinton as the printer. The book was originally

bound in pebble grained cloth and has been noted in purple, brown, red,

and blue colors. Two ornamental blind stamped bands run horizontally across

the covers. Not all of the copies were bound at the printers. Certain of

those sent to publishers were unbound, and this would appear to explain

the fact that there are other bindings which appear to be original but

depart from the binding described. The copies bound by Hinton have the

words “Author’s Edition” on the spine, and the other bindings

seen have not had these words.

Except for a very few minor

word changes, the first edition by Appleton was exactly the same as the

author’s edition. No change was made until the fourth edition when a preface

written by George was added and a quotation preceding a chapter formerly

credited to an Old Play was given its true authorship, Edward R.

Taylor. From this point on there were no revisions, although certain of

the foreign printings were abbreviated.

If ever The Zamorano

80 is supplemented (and life being what it is, it will be), Progress

and Poverty can well be what it is in the Grolier list, number 81.

It seems fitting to close

with a quotation from Dr. Taylor made shortly after George’s death.

When Progress and Poverty

was in process, as upon its completion, it occurred to me that here was

one of those books that every now and then spring forth to show what man

can do when his noblest emotions combine with his highest mentality to

produce something for the permanent betterment of our common humanity;

that here was a burning message that would call the attention of men to

the land question as it had never been called before; and that whether

the message was embodied in an argument of irrefragability or not, it was

yet one that would stir the hearts of millions.14

NOTES

1. Henry George, Jr.,The

Life of Henry George (New York, 1900), p. 289. This work is by George’s

son; and, while it has the usual fault of a biography by a member of the

family, it contains a lot of detail that otherwise would be lost.

2. Robinson, W. W, Land

in California (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1948), p. 157.

3. Robert Glass Cleland,

A History of California: The American Period (New York, 1926), p.

402 et seq. Cleland’s treatment of this period of California history

is the best noted.

4. George, Jr., Life

of Henry George, p. 307.

5. George, Jr., Life

of Henry George, p. 315.

6. Charles Albro Barker,

Henry George (New York, I955), pp. 379, 423, 531, 596, and 627;

also letter to the writer from the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. The

work by Barker would appear to be the definitive biography of George: it

is well written and objective.

7. Alice Payne Hackett,

Fifty Years of Best Sellers, 1895-1945 (New York, 1945), p. 124.

8. Letter to writer from

Random House.

9. Henry George, Progress

and Poverty (4th ed., New York, 1881), p. 357.

10. George, Progress

and Poverty, p. 359.

11. George, Progress

and Poverty, p. 374.

12. George, Progress

and Poverty, p. 479.

13. George, Progress

and Poverty, p. 503.

14. George, Jr., Life

of Henry George, p. 308.

KENNETH M. JOHNSON, a vice-president

of the Bank of America, received his baccalaureate and law degrees from

Stanford University. Besides contributing to various legal and historical

journals, Mr. Johnson is the author of The Strange Eventful History

of Parker H. French; of Aerial California: An Account of Early Flight in

Northern and Southern California, 1849 to World War I; and of José

Yves Limantour v. the United States.

The California Historical Society Quarterly

March 1963

Return

to the top of the page.

|