|

||||

|

||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

By Irving Stone. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin; $3.

FULMER MOOD Oakland born Fulmer Mood (1898-1981) received his Ph.D. in history from Harvard, and taught American history at the University of California at Berkeley. He was a frequent contributor to history publications, and wrote extensively about American regionalism and the American Frontier. Dr. Mood’s review of Stone’s book was published in 1938.

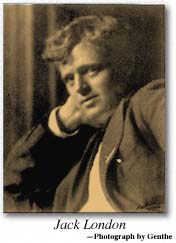

Jack London has been dead almost twenty-two years, and during the whole of this time his literary executors have kept a tight grip, a very tight grip indeed, on his personal papers and literary remains. With such consistency have they pursued this policy of secrecy that the conviction has forced itself into the minds of more than a few persons who have been interested in London and his contribution to American literature that there must be, hidden away, a skeleton in the London close. Mr. Stone is the first individual who has had free access to all of London’s papers and now he comes back to report that the closet holds not one but three skeletons. No wonder, then, that the executors have kept the lid on tight all these years. The first skeleton? Mr. Stone writes that Jack London, born in San Francisco in 1876, was an illegitimate child, son of William H. Chaney and Flora Weilman, and that Chaney deserted the expectant mother, who married John London, a farmer and Civil War veteran, some months after the birth of her baby. The knowledge that he was an illegitimate was always very disturbing to London, Mr. Stone adds, and he did his best to prevent the information from becoming public.

Both of his parents were extraordinary, persons of natural power,

although neither ever made what the world calls a success. The father was

a lawyer, journalist, popularizer of astrology, a man who lectured from

ocean to ocean and wrote voluminously. He sprang from a

State-of-

These are the principal revelations that Mr. Stone offers in his biography, which follows London’s career from its beginning in Oakland, where he grew up as an underprivileged youngster, through hardships of one sort or another and many adventurous experiences in Alaska, the Far East, the South Pacific and the slums of Whitechapel to his eventual immense success as a writer, who earned big money with a prolific pen. He traces London’s stern struggle to obtain an education, showing how he contrived to equip himself intellectually for the career of literary triumph which, from the first, he felt sure would one day be his. Of formal training he had very little at any time, and did very well without it. If ever an American writer was the product of the public library system, and his own indomitable will to learn, that writer was Jack London.

London’s was a robust, magnetic and buoyant personality. Forthright and emphatic in speech, in action and in word, he easily made friends and as easily made enemies. Mr. Stone is at pains to show the most agreeable aspects of his nature, and proves his point up to the hilt, but there was another side of London’s character, and one less pleasant. There is no need today to emphasize it, but it is just as well to understand that a complex being of his sort was no angel come to earth, even though one refrains from citing particulars. At bottom he was generous of spirit and fundamentally kind. Superficially, London’s career would appear to be without order or plan, a series of short, disconnected fragments, each one different somewhat from the preceding one. But Mr. Stone discovers a unifying design beneath the seeming disorder. Here is his thesis. London learned of Socialism during the depression of 1893. He applied these radical theories in his writing, which thereby gained in power and clarity. For twenty years or more, in season and out, he preached Socialism, then later resigned from the Socialist party alleging that it was too tame and too passive. But if London wanted to out-Marx the Socialists, why then did he vote for the Republican Hughes in 1916? He publicly supported the Allied Government in their war against the Central Powers; he did not join with the pacifists of the day in condemning the European war. No, Mr. Stone’s thesis is too simple. The truth is much more complicated. London’s interest in and connection with Socialism had been on the downgrade from the time when, in 1909, he came back from the South Seas. This diminution of interest reveals itself clearly in his later books, but Mr. Stone prefers not to see the new phase; it would damage his neat pattern. The ballot for Hughes and the plot of The Valley of the Moon (1913) destroy the cogency of the biographer’s interpretation.

Mr. Stone has succumbed to the vice of extravagant paraphrase. It is often difficult to know whether the material on a given page was written by Jack London or Irving Stone, so liberally does the biographer lift, adapt and make over extracts from the writings of his subject. This easy, this all too easy, method of composition has dangers. Mr. Stone has not escaped them, for when he relies on autobiographical remarks stemming from London himself, the biographer takes them over uncritically, errors and mistakes and all. Abundant examples occur to show that Mr. Stone did not verify the material that he so freely availed himself of. From the publishers’ blurb one learns that this is the “definitive” biography of Jack London. Let’s take them at their word, then: The “definitive” biography consists of an obvious thesis crudely worked out, and three ancient scandals. It exhibits a fair acquaintance with the subject, and ought to make a super-colossal Hollywood scenario. In: This World, Vol. 2, No. 21 San Francisco Chronicle September 11, 1938 Note: Jack London’s father, William Henry Chaney (1821-1903), was author of Chaney’s Primer of Astrology and American Urania, published in 1890 by Magic Circle publishing, St. Louis.

Gladys Hansen Review of Jack London biographies

|