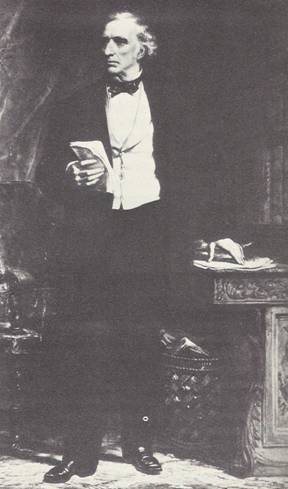

Who was Cornelius Kingsland Garrison--the man who outmaneuvered the powerful

Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt for control of a steamship line, and later,

during his term as mayor had given away his salary to the orphanages of the

city?

This

self-made man started out as a cabin boy on Hudson River sloops and later

graduated to command a steamboat on the Mississippi. When gold was discovered in

California, in 1848, he had shrewdly gone to Panama, where he opened a gambling

house, and other businesses, all of which prospered from the traffic that

crossed the isthmus.

This

self-made man started out as a cabin boy on Hudson River sloops and later

graduated to command a steamboat on the Mississippi. When gold was discovered in

California, in 1848, he had shrewdly gone to Panama, where he opened a gambling

house, and other businesses, all of which prospered from the traffic that

crossed the isthmus.

He arrived in San Francisco in March of 1853 as agent for the Nicaragua

Steamship Line, formerly the Vanderbilt Line, which was then in a state of

collapse from mismanagement and accidents. Within six months he made the line so

fiercely competitive with other carriers that earnings rose sharply.

At this point in his business career Garrison was recognized as being so shrewd

in his business dealings that if you dealt with him “you should first set 20 men

to watch him.” Many businessmen felt the city might appreciably prosper by

making him mayor, especially if he could work some of his financial magic on the

city’s problems. It seems amazing that a man could move so quickly into the

political spotlight when a resident for only seven months. However, when the

nomination was offered, Garrison accepted. Being a wealthy man he waged the

city’s first “monied fight,” won, and began office as San Francisco’s fifth

mayor on October 3, 1853. Garrison was San Francisco’s fifth mayor, but the

fourth man to serve in that office as Charles Brenham had earlier been elected

to two separate terms.

Within two weeks after Garrison’s election in September he witnessed the

completion and operation of the first telegraph line in California. This line

covered eight miles, between Point Lobos and the financial district and brought

news of approaching vessels, cargo, and point of debarkation. Such news was

vitally important to the auction and commission houses that flourished in the

city.

Almost immediately citizen Garrison along with some friends began speculating in

real estate by purchasing city water lots and city script which was then afloat

at a very low market price. Later as mayor, Garrison became the prime mover in

bringing about the sale of these lots. Unfortunately, this transaction cost the

city dearly as it was compelled to buy back these same lots sold earlier at

speculative prices because it could not give title to the purchasers.

Apparently the citizenry were willing to overlook Garrison’s action concerning

the sale of the water lots, but they reacted in unison against him when he

suggested that gambling and Sunday theatricals be abolished. Obviously,

corruption in politics was one thing and their fun another.

It seemed the new mayor was off to a bad start but he quickly offset his earlier

actions by demonstrating great interest in education. He obtained funds from the

Common Council to build schools so that students would be properly housed

instead of remaining in shanties and shacks. At one point when public funds were

exhausted he made certain the school was completed by contributing his own

money. He also established the first school in San Francisco for children of

African parents. They had not previously been given an opportunity to attend

school, primarily because most could not afford the tuition. Garrison also began

the first industrial school for problem children, for he was very displeased

with the practice then followed of housing delinquent and abandoned children in

city jails or poor houses.

The fire department’s budget was sharply increased under Garrison and new

firehouses added as well as seven new cisterns built at important street

intersections. One of the main reasons for failure in fire fighting was the

shortage of water, and cisterns spotted throughout the city help immeasurably.

The uncertainty of the cost involved in traveling by carriage cab in 1853 drew

Garrison’s ire. With no city regulations governing fares, most cabbies charged

according to whim and demand of the moment. San Franciscans refused to pay more

than a moderate price but our visitors were often “taken for a ride.” The mayor

initiated the first control over the carriage cabs. In addition, Garrison was

the first mayor to ask for a tax on nonresident capital. He had hoped to

increase city revenues by taxing the millions of untaxed dollars that passed

through our financial houses for accounts held by foreign stockholders in mines

and industry.

In order to increase interest and investment in city businesses, Garrison called

for completion of a transcontinental railroad and a transcontinental telegraph

line. However, when asked by Collis P. Huntington to invest in the railroad,

Garrison replied “The risk is too great, and the profits, if any, too remote.”

San Francisco was by the end of 1853 divided into eight public wards for

political purposes, had 250 streets with posted signs, two public squares, ten

public schools, 38 large cisterns for storage of water, resident consuls for 27

foreign governments, two hospitals, a philharmonic society, five theaters, and

something no other American city had, a Chinese interpreter in the Recorder’s

Office.

On February 11, 1854, the city took a most important step toward civic

improvement with the installation of streetlights. There were 84 in number and

were lit by gas provided by a plant located at First and Howard Streets. If the

city could finance streetlights, then certainly Portsmouth Plaza, then a dusty

lot, could be made more attractive. Garrison urged money be appropriated to

plant flowers and trees. After all, this was a historical site, for it was here

that Capt. Montgomery first raised the American flag on July 9, 1846.

Not all of Garrison’s time, while mayor, was spent attending to the various

civic projects he championed. He had little patience with the high crime rate

and was well known for his personal acts of heroism against vandals or

lawbreakers. A typical example involved a fence constructed at the direction of

a Mrs. Latimer across Merchant Street one dark night. The woman claimed she had

not been properly reimbursed for the street after she sold it to the city. The

city marshal refused the next day to remove the fence. Local businessmen grew

increasingly irritate at this latest interference with commercial life and

complained to the mayor. He immediately went to the barricade and personally

removed it, in the face of some opposition, after which he fired the marshal for

his failure to handle the situation.

When the annual state and city elections came up in September 1854, Garrison

felt confident enough to run for re-election. The city had done well under his

administration, many new civic projects had begun and the economic slump of that

spring and summer had eased. He probably wouldn’t have been so confident

concerning his re-election had he realized the strength of the newly formed

“Know Nothing Party” whose membership was restricted to native-born Americans,

who were non-Catholics. They, by sheer force of numbers, and by proper

organization, were able to sweep party members into nearly every city office.

The only office in doubt was that of mayor. The counting of the ballots

continued for five days during which time there was much talk of ballot-stuffing

and fraudulent counting. On September 11, it was announced the city had a new

mayor. Stephen P. Webb had won by 539 votes.

In 1859 Garrison returned to New York City for business reasons, but ten years

later his visit to San Francisco via the overland train gave the city cause for

a great celebration.

The fifth mayor of San Francisco, Cornelius Kingsland Garrison, died May 1,

1885, in New York City. His contributions to this city are many, important, and

varied. They include his far-sighted proposals and actions on schools, juvenile

problems, including the “industrial school,” fire protection, city

beautification, and increased tax revenues.

Regardless of the financial corruption that may or may not have involved

Garrison personally, his term as mayor was outstanding for its contributions of

some abstract principals known as “enlightenment” and “humanitarian.” Garrison

set a pattern for many future generations of San Franciscans when he placed so

much emphasis on individual contributions to building a better city.

If, in the 1850s, San Francisco was to compete with the major cities of the

world, it could not afford the luxury of many decades in which to catch up.

Cornelius Kingsland Garrison, the fifth mayor of San Francisco, was no paragon

of virtue, nor was San Francisco virtuous.

Garrison was the man for the times.

Gladys Hansen

City Archivist Emeritus

City and County of San Francisco

July 2007