|

San Francisco author and historian Bailey Millard (1859-1941) wrote the “History of the San Francisco Bay Region : History and Biography,” published in 1924 by the American Historical Society. He penned this dramatic eyewitness account of the evacuation of the City shortly after the earthquake.

THOUSANDS FLEE FROM BLAZING CITY

BY BAILEY MILLARD

Like the story of the flight from Pompeii is the story of the flight from San Francisco. True, it was not amid flying scoria that the multitude made its way from the city, but amid a rain of falling cinders, in blinding smoke and a heat that beat over the earth like the heat of the day of judgment. The rush of the grand army of refugees was not so great toward the Presidio as has been reported, but down the neck of the peninsula toward San Mateo and Redwood City, across the bay to Sausalito, San Rafael, Tiburon, Napa and Petaluma, and greatest of all toward Oakland, Berkeley and Alameda, the eastside suburbs beyond the harbor.

As they could not go by way of Market Street, the old-time channel of travel, nor by any other street to the south of Telegraph Hill, the refugees scrambled in a headlong flight and in a thick, turbid desperate stream down Union, Green, Chestnut and other northside avenues until the crowds all met and fought their way down the crammed and choking throat of Bay Street. Never on Fifth Avenue or Broadway have I seen such a surging tide of humanity as that fighting its way down dusty Bay Street, past the shattered warehouses that had tumbled their heaps of bricks into the road and piled the way with masses of fallen timber.

Automobiles piled high with bedding and hastily snatched stores, tooted wild warnings amid the crowds. Drays loaded with furniture and swarming over with men, women and children, struggled over the earthquake-torn street, their horses sometimes falling by the wayside in a vain effort to pass some bad fissure in the “made” ground. Cabs, for which fares at the rate of ten to twenty dollars a piece had been paid in advance, dotted the procession, and there were vans, express wagons of all sorts, buggies and carts, all loaded down with passengers and goods. But by far the greatest amount of saved stuff was being borne along on man- back and woman-back, and even child-back. I saw one little girl of six or so struggling with a big bag of provision, the sweat streaming from her little red face and her eyes strained and tearful. Great troops of Chinese were there, even the little-footed women, and all heavy laden. They were on their way from the Presidio, which they had left on the false report that no provisions would be dealt out to Asiatics. Girls of ten or twelve were carrying little Orientals in slings on their backs.

“City all gone,” said one old Mongol with stoic face, “but Oakland be all right. Me go Oakland. Catchee here, grub there.” Japanese pulled trunks along the splintered pavement or carried their satchels and bags on their back. I saw two Jap girls with a long board running from the shoulder of one to the shoulder of the other, from the middle of which depended a heavy sack of stuff. The board was bending and swaying and it must have hurt their backs, but they were fanning and smiling and chatting with their companions. A band of Italians, men and women, passed along the way. The women carried baskets on their heads, while the men strained under terrible burdens. A little further along I overtook two men and three women who had adopted a strange mode of carriage. They had their goods tied to a long ladder, which they were pulling along the concrete. One woman ran ahead and thrust rollers under the ladder and then ran back and gathered them for another fifteen feet of progress while the queer team halted. All along the way men lay on the sidewalk or in doorways, some resting, some sleeping, some drunk.

Some of the tired refugees had already walked miles and would have still other miles to traverse before they could reach the ferry. Wild talk ran back through the crowds that the ferries were all closed, and all were assured that if they did not get aboard none of them might return to save women or goods. We passed a great campground near Telegraph Hill, where many of the refugees had halted and would go no farther. It was patrolled by soldiers. The vacant lot was swarming with broken- down outfits. Men were making little tents of sheets and blankets, held up with sticks taken from collapsed buildings. It was not such bad going for the wheeled vehicles until Pier 22 [The Embarcadero at Folsom St.] was reached. There the enormous fissures, only partly bridged over by planks and boards, made the travel very difficult. Auto tires crashed down into the rents and wagons were overturned. In the grime and dust and some and under the grilling heat, the foot passengers made their way and the drivers cracked their whips over the backs of the horses, whose red tongues stuck from their mouths.

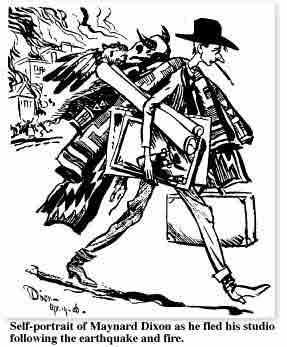

I met Maynard Dixon, the artist, coatless, and sweating, tugging away at a little child’s wagon on which was piled all that he had saved from his burnt studio. By his side walked his wife, loaded down with luggage. Dixon had helped to save his artist friend [Xavier] Martinez, upon whom the first quake had showered a pile of bricks. I met Maynard Dixon, the artist, coatless, and sweating, tugging away at a little child’s wagon on which was piled all that he had saved from his burnt studio. By his side walked his wife, loaded down with luggage. Dixon had helped to save his artist friend [Xavier] Martinez, upon whom the first quake had showered a pile of bricks.

Nearer the ferry it was treacherous walking, past the tumbled or crazily leaning warehouses. In some places the curbing had dropped completely out of sight. Freight cars, topping half over from twisted side-tracks, stood on billowy ground and were full of tramps and toughs over which the soldiers kept watchful eye. A little farther along and the great ferry building, the finest in this country, was seen, with its leaning flagpole; and still a little nearer, and the smoking ruins of the lower business section were seen. One could hardly tell where Market street had been. A line of silent fire engines was passed, and we walked by the smoke-grimed harbor front palms and were in the great depot. Here the masses of refugees thronged the wide walks and crushed into the waiting rooms. Some of them had been waiting for hours for a chance to cross the ferry. All were told that they might go in their turn, but that none might return. Relief men with badges met the wayfarers there. They were representatives of the suburban towns, where committees were awaiting the fleeing ones to shelter and feed them. From time to time cheers went up when the relief people told the refugees of the aid that awaited them. I had come to the ferry not for flight, but to deliver a message, and soon I was on my way back afoot toward the Presidio, near which I had three women and two children to conduct from a threatened house and aboard a launch bound for Berkeley. We were two hours waiting for gasoline for the launch, and all the time the cinders fell upon us and the smoke poured over us, while the red glare of the burning houses was reflected far out upon the dirty, ash-strewn water of the bay. Our launch man finally appeared, carrying a five-gallon can of benzene, for which he had paid $5, and when this fuel had been poured into the tank we started down the bay passed dismantled piers. The evening sun shone red through the pall of smoke which streamed far out of the Golden Gate. About us was every conceivable kind of craft, full-freighted with refugees, bound for Sausalito, Belvedere, Tiburon, Napa and other places, and many going our way. Tugs shrieked sharp warnings, boatmen called aloud and from two junks, crowded with escaping Chinese, there was a hubbub of voices. We passed lateen-sailed fisher boats, loaded down with Italian voyages, shouting to each other. We passed five tugs on which

dead-beaten firemen lay stretched in slumber, and so on down to Goat Island and across to Berkeley, a peaceful haven of refuge, where Christian men and women were eager to administer to us and kindly men offered us rooms in their houses. When I told them all that we were able to pay for our food and shelter, they still insisted on giving them free of charge.

“You are able to pay today, but you may not be tomorrow,” was what they said, and this was true, for not a bank in Berkeley was open to cash a check for me, and none would be for four days.

The train that had borne us up from the pier was surrounded with a clamoring crowd, eager to get to the city, but no one was permitted to go aboard.

“I have a wife and two children out on Franklin Street,” shouted one desperate man who clung to the rail and had to be fought off. “I must go to them and save them.”

“I’ve got a wife over there somewhere, too,” said the guard, “if she’s alive, but I can’t go to her.”

Return to the earthquake eyewitness accounts.

Return to top

of page

|